As the pandemic transformed everything about MAPC’s place-based work, staff sought new ways to process and understand what we were going through. We sought ways to reflect and be in conversation about uprisings for racial justice unfolding across the country, including in the cities and towns we call home in Greater Boston. What did it mean for us, as both professionals who work in community development and as community members with obligations to each other – to live through this moment? Over the winter, a group of three staff – MAPC Equity Team Co-Chair Patrice Faulker, Iolando Spinola and Emma Boast – teamed up to create Reimagining the Region, a participatory, digital public art project that invited MAPC staff to share their visions for an anti-racist Greater Boston.

In May, Jenn Erickson, MAPC Director of Arts & Culture, interviewed the project creators and explored the project’s impact on the agency. The following is a transcript of that conversation, condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Bios

Jennifer Erickson: We're really excited to have a space to have a candid conversation that delves into emerging arts and racial equity initiatives that we’ve been working on at our agency, namely the project called Reimagining the Region. How did this collaboration [on Reimagining the Region and creating the Museum of MAPC (MoM)] emerge? You may have different memories, so I'd love to hear your different recollections.

Patrice Faulkner: I have an origin story. The idea of Reimagining wasn't just me. It was a day that I was having lunch with a former MAPC staff member, Seleeke Flingai. We were finishing up a project and he was like, hey, I wish there was a way we could reimagine how we view black women in society. And I was like, I feel you, you're right. I wonder how we can do this? It was an idea, but after sitting on the proverbial shelf for maybe a year and a half or so, it just got built upon.

Iolando Spinola: Patrice pulled me in. After attending an Equity Team meeting where we were brainstorming how we could have the whole agency do some reflection to reimagine how people of color can best impact planning and be more centered in their communities, I decided to support Patrice in trying to execute whatever came out of that conversation. And that's what led us to the project, and then Emma was able to join and support us in some big ways.

Jennifer Erickson: And can you very briefly share what the Equity Team is for folks who don't know?

Iolando Spinola: Yes, the Equity Team is a cross-disciplinary group of staff from different parts of the agency who are part of a working group focused on the topic of equity. When we think about equity, we're talking about racial equity, we're talking about gender, we're talking about all the different demographic pieces where we know there's been some historical injustice. We're thinking about how can we make sure people are living and are treated with dignity in workplaces and in our region.

Patrice Faulkner: Yeah, our committee promotes internal and external equity at MAPC.

Emma Boast: My recollection is that we were all working remotely. When I joined this project, I knew it had emerged out of an in-person conversation. But by the time I learned about it, we were all in our homes, where we've been in for over a year now. And I remember talking with you, Patrice, and hearing this idea, and realizing that we'd also been having discussions within the Equity Team about how we could help cultivate staff engagement in the agency, recognizing that we're all isolated and going through this difficult time, and use that to do that reflection that you were referencing in terms of living through this pandemic and witnessing and experiencing protests for racial justice. What does it mean to be able to process that as a staff, as colleagues, and as friends, when we’re all separated? Patrice and I got to chatting about how this could also be a way to build those connections across staff and cultivate conversations about race and racial justice in new ways.

Iolando Spinola: The racial reckoning that happened in the summer of 2020 was what propelled us on this project and got staff at the agency talking about the topic and interested in reflecting and processing and reimagining a new future. That was a big catalyst to allow us to move forward on this project.

Jennifer Erickson: A lot of organizations were putting out statements with the death of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others - MAPC included. But what would you like to say about what the feeling was internally within the culture of MAPC and within the Equity Team? Why did you all think that this project needed to happen, and particularly as an internal initiative?

Patrice Faulkner: I was thinking during that time, are we who we say we are? Is our narrative matching up to what we tell everybody else? When we're thinking about equity, are we putting equity in our thoughts completely? Are we pushing things far enough? What are our personal narratives around race?

Iolando Spinola: There's just so much going on that we needed space to think through and to process some of these different things that were happening. We were putting out statements as an agency, along with a whole bunch of other organizations. Those statements came out from leadership crafting the perfect message. But a lot of staff, myself included, wanted to time to process and to do some collective reflection with each other to process some of the stuff that was happening nationally. This project started to do that for me, and some other staff utilized the space and the opportunity that we made available to do some of that self-work and self-reflection, to see how that connects to the overall work that they are doing and the work that the agency is doing.

Emma Boast: This is not just work, we're at home. There's this blurring of boundaries that was and continues to be confusing at times. But that also has opened up a space where we can encounter each other as fellow people and not just as colleagues. That's part of what this project was about too, recognizing that you can't disentangle your own position, say, for me as a white person doing this work, from my day to day lived experiences outside of work. What does it really mean to grapple with that, and not separate myself from questions of what equity means and what justice means?

Jennifer Erickson: I want to pause and talk a bit about creativity at MAPC. We gave people billable time so that they could have some actual time during the day to make a contribution. We value people's creativity at MAPC, but it tends to be really hard for folks to feel like they can be [creative], because the agency runs on billable time. Every minute of our time is accounted for with a code.

Iolando Spinola: There was a diversity of the types of contributions that we received from staff. Some folks recorded videos, some people incorporated music, some people created really visually stimulating pieces. Some folks found pictures or they took pictures. Folks even had their families get involved in their contributions. There was a diversity of staff by department: planners from Land Use, Economic Development, Clean Energy, and my own department, Strategic Initiatives.

We, as an agency, often ask folks to think about what a more equitable future might look like, three years from now, 30 years from now, or 300 years from now. We decided to focus on 300 years from now, because planning rarely ever plans that far ahead. So we want to push people to think that far ahead and allow folks to be creative and think outside the box.

It was hard for some folks to think creatively and think without a lot of the boxes that we put ourselves into sometimes. And it was cool to see some of the different projects and some of the different contributions from staff who were outside their comfort zones when it comes to creating these different products. We pushed them and we made spaces available for them to think about their projects, using office hours where we brainstormed with them, and we gave them different tools and techniques for them to think about what they could contribute.

Patrice Faulkner: We had [virtual] drop-in hours twice a week, and we spread ourselves out so that one or two of us could be there to give guidance. If people wanted to ask questions or needed resources or additional guidance, or if they just wanted to talk to other folks who were working on this too, to flesh things out – we made our time available. They could use a billable code to be able to use this drop-in time to figure things out. When I was in the drop-in sessions, you could definitely see the sharing of ideas. And also, depending on who was in the room, the different dynamics at play. You could see people wanting to share what they were thinking about, and just thinking about different abstract concepts that they wouldn't normally think about or talk about in their departmental meetings.

Emma Boast: Yeah, each [drop-in session] I went to played out a little differently. We also had some one-on-one conversations with people. Some folks who came to the drop-in sessions wanted to workshop things further or maybe didn't totally feel comfortable sharing their ideas in a group setting, so we tried to make individualized support available for folks. Each drop-in session had a slightly different dynamic. I remember one was very much an ideation space with people sharing their ideas, and then riffing live and in the chat, sharing and building on each other's ideas and bouncing things around. And then there was another session I was in where we got into big philosophical questions like, what does it even mean to think about the concept of anti-racism or an anti-racist region 300 years from now? What is race? What is the history of race? How did we get to where we are now? And what does it mean to think centuries out? It depended on who was in the room and what people were interested in talking about. I wouldn't say that everyone who participated in one of those [drop-in] sessions ended up submitting, but my view is that was still participation. The conversations that we had in the drop-in sessions were just as valuable as any project or product that people might have shared through the submission process.

Jennifer Erickson: I attended the [virtual] gallery opening where people shared their art. I remember that some of them were so emotionally moving, and that some of us admitted that we cried while we were watching people share their work. You said after the opening – and it came up during [the event] – that people felt like they had a draft, or a draft of an idea and were wondering, “should I share this? I don't know if it's really ready.” And I think you all coached them to just share it like it is. Because is it ever really going to be done? Do you want to say anything about that process?

Patrice Faulkner: What does “done” really mean? I don't think that drive for a concept of perfection was necessary, or even is necessary at all. Do you feel in your heart that what you did conveys your feelings about what is anti-racist and about what an anti-racist future looks like? I was with you, Jenn, when we were talking afterwards and I noted that 25 of us were in the same space talking about race, and there were no “ouchies.” To my knowledge, there were no “whoops” moments; we were all in the room, in a vulnerable space. Because most of us created something that says “this is who I am in an anti-racist future. I'm not just saying what it looks like to me, but I'm telling you who I am in this anti-racist future. I'm being vulnerable with you, so you can be vulnerable with me, and I will forgive you. I see you. And we can have an honest conversation about what's happening, and we can truly see each other in this moment.”

Jennifer Erickson: Yes, that resonates so much with me. Because I was seeing people in a way that felt so much more real. When we talk about equity, it can feel like an equity exercise sometimes. But it felt very, very personal. And people were taking it to this place that I'm imagining feels scary and risky. I come back to a lot of what you're saying – we often ask people outside of [MAPC] to do these visioning processes. And for us to do this with this subject matter is great because it's pushing us to realize that if we're ever going to really push this work more as an agency, we have to continue to stretch our own comfort levels and speak honestly with each other.

Who wants to talk about the MoM and how people shared their submissions?

Patrice Faulkner: The MoM is the Museum of MAPC. It is completely a play on the MoMA in New York, but we're calling it the MoM. People submitted their work via SharePoint. And we were able to take the items in SharePoint and put them into a Slack channel dedicated to showcasing the creative works of MAPC staffers.

Emma Boast: We had a few ideas for how to create a digital exhibition. Initially, some of our ideas were a more digital translation of our traditional conception of an art exhibition – a gallery with art statically hung on the wall. Nothing felt like it was really sticking. Patrice, once you raised the idea of using Slack, it clicked into place. Why wouldn't we use this tool that many of us at the agency use for informal conversation? We're already sharing articles and ideas with each other, so it’s a natural space to continue the conversation and to frame the submissions in a space that allow people to react and interact.

Jennifer Erickson: Could you share your work just as one example, and explain it if you wouldn’t mind?

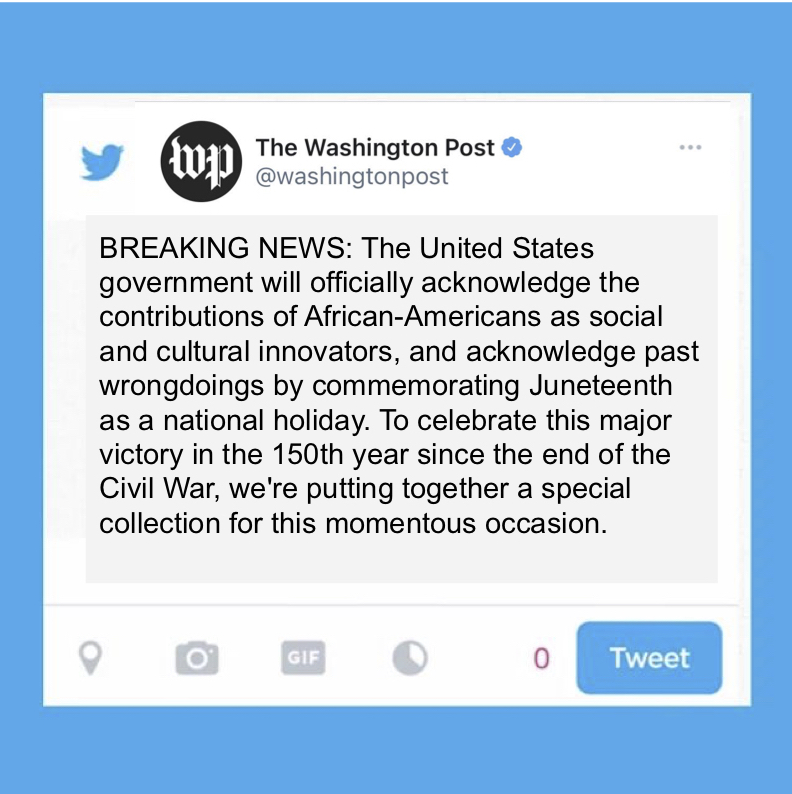

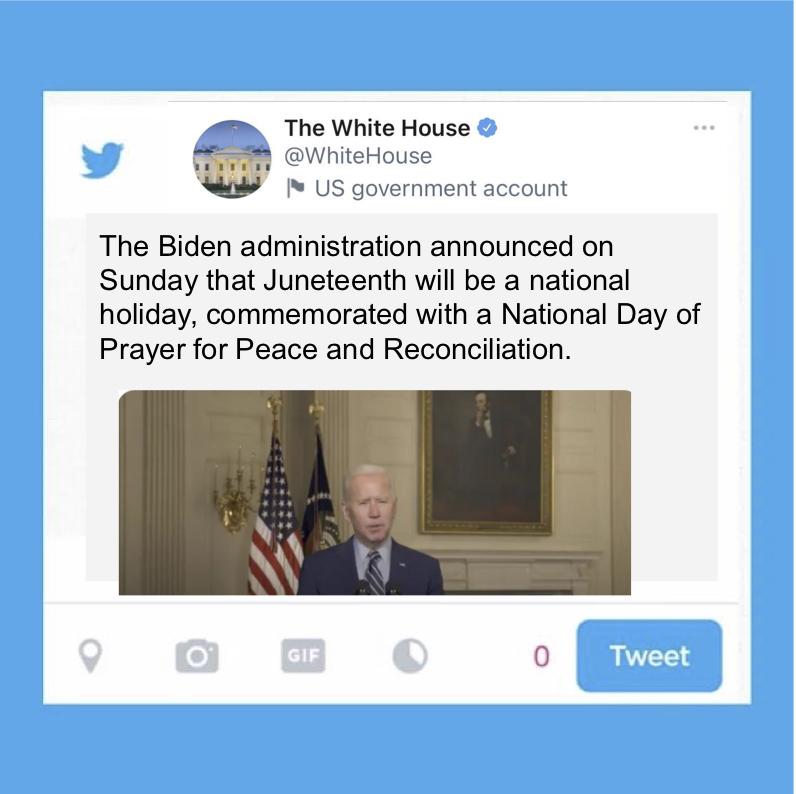

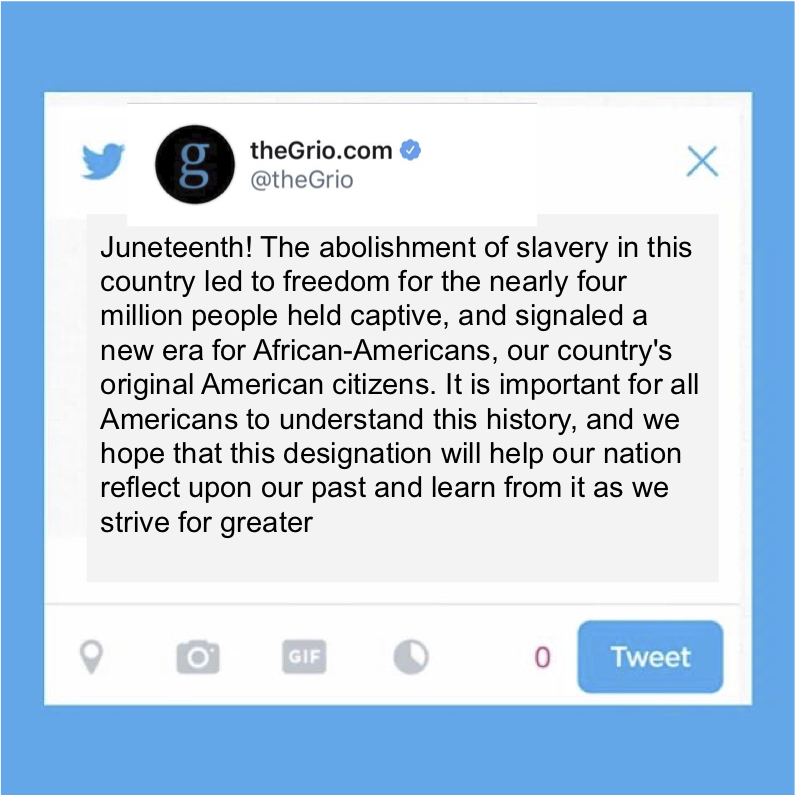

Iolando Spinola: Yes, I can definitely do that. I wanted to make sure I participated in this because I was asking staff to contribute something. And I wanted to take the time to think about what [an anti-racist future] looks like. I decided to focus on what would it look like three years from now in a slightly more anti-racist future. I thought about it in terms of what social media could look like.

I honed in on Twitter, because I'm a big fan of Black Twitter and that whole cultural phenomenon. I decided to think about new technology, specifically artificial intelligence and natural language to see what would happen if I used software that's readily available online to help me create this anti-racist future three years from now. I wanted to know, what would Twitter look like if Juneteenth actually came to fruition? Junteenth is a day to celebrate the emancipation of African Americans in the United States, and I wanted to know what it would look like if Juneteenth was a federally recognized holiday?

So I used an ai tool to insert some specific prompts and add some terms, and then the algorithm helped me draft tweets. It was an experiment to see how our communications infrastructure, like Twitter could reflect that potential future?

I presented it to staff, and it was slightly outside my comfort zone. But I got a really good reception from people on the MoM, the Museum of MAPC, and when I presented it to them at the opening event.

Jennifer Erickson: I'd love to hear from all of you what feels different for you having participated in this project? What's your sense in talking to other people who participated and how they feel about it? I know you all have some ideas for what's next.

Patrice Faulkner: Since I've participated in this whole process, I feel braver in being creative and expressing different ideas and concepts. I think about how things can be different and about what structures serve and what structures don't serve, and also how to communicate that to other people in meetings. The idea that no concept is so outside [the box] that it can't necessarily be said in a meeting. I feel a lot braver and a lot more confident in presenting those ideas, which actually are good ideas.

Emma Boast: I learned so much about my colleagues. That's something I hope we can continue through the MoM, or through other kinds of engagement activities that we might dream up together. I think it makes for a more human workplace and frankly, for me at least, more impactful work.

Iolando Spinola: I definitely appreciate the reflection space and opportunity to connect with staff in a more vulnerable way to share a little piece of myself with them. Doing that reflection with staff helps build some of that social capital and some of those cultural pieces that are necessary to give us a reason to go to work (other than all the other reasons: to make an impact in our communities to make sure we're generating income for our families). It's also good to go to work to express yourself and give a piece of yourself in a creative way. That space allowed us to do that a little bit. And it was fun and interesting. And I hope that we continue to make these experiences available to staff at our agency and that other organizations start to think about how can they allow folks to be creative and share themselves with their fellow colleagues.

Jennifer Erickson: Let's continue to unpack our reflections on what things are staying with you as you think about the continuation of racial equity, creativity, and culture shifting at MAPC?

Patrice Faulkner: There are structures in place that do not serve us any longer. “Reimagining the Region” is helping me think about how structures can be different. For example: what structures in the Greater Boston area are needed, and is there a better way to approach them? It has me thinking specifically about the structures of public safety and policing, and how those can be changed. How can we reimagine what those are and think about them? “Reimagining the Region” has also helped me think about what we can actually do and what is really necessary. What is serving everybody, and what is just serving the one percent?

Jennifer Erickson: One direct way in which MAPC is part of the public safety community is through our work with the Greater Boston Police Council through our Municipal Collaboration Department.

Emma Boast: I have also been thinking about which structures we're interrogating and trying to dismantle through this project. For me, it is what you just said Patrice, and I’m also thinking about what participation means. For example, in the context of a visioning process, a public meeting, or anything where we are asking people to participate in our processes – what are we asking people to do? What is that participation in service of? Who is designing those processes in the first place? What are we doing with that information? How does it serve people, not just serve us? What does it mean to have reciprocity in planning? And how can we think beyond participation, or rethink participation?

I recently read this interview between two planners and advocates, Tamika Butler and Justin Garrett Moore, who were talking about participation and the emotional labor that it requires, especially for people of color, and how that plays out in planning and community development work. That is a pressing question that I'm continuing to take with me. What does it really mean to dismantle how we think about participatory planning and critically interrogate that and who it serves?

Iolando Spinola: One thing that this project allowed us to do, too, is reflect on what can be done at work, because sometimes we think that being creative or sharing our authentic self at work is not completely appropriate. I’ve had that thought; I have imposter syndrome that I'm dealing with, in trying to grasp being a person of color at MAPC. This project allowed me to do some reflection and some work around that. I think that’s a good use of time and a good use of agency capital. I think it gets the agency to think about the work a little bit more than has been historically done. I'm happy that the agency made space and made room for us to do this as staff. It's benefited me, and I know it's benefited some other folks who took part in this project. It's a hard thing to measure. But I'm hoping we can document some things that can show the benefit of projects like this at our agency.

Jennifer Erickson: Yes, definitely committed to that. I'm committed to that. And I appreciate all of you for being honest and vulnerable in this conversation.

M

M