Chinatown Story Cart

An Interview with Crystal Bi Wegner and Lily Xie

Developed in partnership with Asian Community Development Corporation, Chinatown Story Cart is a participatory public art project that collects stories from the Boston Chinatown community and showcases it in visual media. Responding to Boston Chinatown’s history as a community whose land and vitality are constantly under threat, the Story Cart activates the memories of residents through artistic methods of storytelling to drive community stewardship and negotiate neighborhood identity in the public realm.

Inspired by the project’s echoes of conversations within the Arts & Culture Department about remembering, MAPC staffers Emma Boast and Dan Koff sat down with Lily Xie and Crystal Bi Wegner, the artists behind Chinatown Story Cart, to learn more about how this project engages with the layered histories and experiences of Boston’s Chinatown.

Daniel Koff: By way of introduction, could you tell us what brings you to the work of storytelling, placekeeping, and community arts?

Crystal Bi Wegner: My interest in storytelling and community arts comes from working with students in Boston public schools. Storytelling provides a rich ground for creating visual art—for example, drawing something and then seeing what memories emerge from that process. The first storytelling project I did was in collaboration with another teacher, Marilú Alvarado Hernandez at the Margarita Muñiz Academy, where we were documenting stories coming out of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria.

Lily Xie: I grew up in the Midwest near Chicago. My parents are immigrants. When I think of storytelling, I think about my family. Storytelling was this big part of growing up, and my family is from a lineage of immigrants: my grandparents are immigrants to China, and my parents are immigrants from China to the U.S. So, I think that storytelling has always held a big place in my life.

In terms of the work of placekeeping, Crystal and I were both participants in a program called Residence Lab, which is a creative placekeeping program run out of the Asian Community Development Corporation (ACDC) and Pao Arts Center [part of the Boston Chinatown Neighborhood Center]. Residence Lab was a program that brought together artists and Chinatown residents to work on a project that activated a park in Chinatown, and that’s how I got introduced to the work. I haven’t stopped since then.

Emma Boast: Thank you for sharing those experiences. Can you tell us a bit about your experience as collaborators: how did you first come to work together?

Crystal: I think we met in 2017 at an art fair. Lily was doing some illustrations and I went up to her table. We started collaborating on Moon Eaters Collective, which was an anthology of queer AAPI [Asian American and Pacific Islander] stories and artwork that we produced through a zine and events. It was a great way to build community through storytelling and through artwork. From there, we started working on Residence Lab, which was a placekeeping residency at ACDC. That residency was special because we were partnered with community members to make artwork. The driving force wasn’t the vision of the artist; it was the vision of what community members wanted to see in their space, and building from their knowledge to realize that. That experience changed the way that I wanted to create artwork—to be more collaborative and grounded in a specific community and history. After that experience, we wanted to continue working with community members in Chinatown. From that residency, which was in 2019, we started thinking about what the Chinatown Story Cart could look like.

Emma: Let's dig into that project. Can you share the backstory of how the Chinatown Story Cart got off the ground? What was the project’s relationship to the neighborhood and place that is Boston’s Chinatown?

Crystal: The impetus was really continuing to work with community members in Chinatown after Residence Lab. As I recall, Lily and I were walking through Chinatown, and a lot of people recognized us and stopped to say hi. We didn’t want to lose those connections; we wanted to keep building on them. Initially, we conceived of the Chinatown Story Project as a pop-up story cart. The idea was inspired by youth advocacy groups, who had created pop-up libraries in reaction to the lack of civic infrastructure (specifically the lack of a public library) in Chinatown—which is directly connected with the history of how Interstate 93 was built through the neighborhood. That's why we conceived of the Story Cart as a pop-up library. It wasn’t a new idea; it came directly from young people’s advocacy.

Lily: The Story Cart project was really a continuation of the work from Residence Lab. There was one workshop we facilitated where we talked about Chinatown’s history. A lot of that history was new for me—and a lot of it was new for the residents in the workshop, too. I realized that you can live in a space and not know anything about how that space came to be—and sometimes that is by design. This aspect of storytelling—understanding the place that you are in—can be a powerful as a way to spotlight different aspects of your community, your neighborhood, your own history, yourself. That was the idea and the energy that we carried into the Story Cart project.

Emma: That linkage between the personal story and collective story—both rooted in place—comes through in the Story Cart project. It’s a compelling aspect of the project. With that in mind, what does placekeeping mean to you, and how did that idea inflect the development of the project?

Lily: When I think of placekeeping, I think of it as a response to placemaking, which suggests that art and culture can form the personality of a place. In contrast, the idea of placekeeping, which comes from Roberto Bedoya, is as a way of honoring the people who already live in a place and a way of acknowledging their history, culture, personality, and struggle. This reframing demonstrates how art and culture can honor the cultural fabric of a place.

Crystal: I'd add to that placemaking and placekeeping are active; they show that community members can have an effect on the future of their community. They have agency over how they're understood, how they understand themselves, and how they project that identity and that personality into the world. Placekeeping builds collective knowledge through art and storytelling—knowledge about how we relate to each other and how we can care for our spaces.

Emma: I love that framing of agency, and saw that in some of your writing where you noted capacity-building as an important aspect of this work. Thinking about local capacity, can you describe the different partnerships and relationships that informed the work and that grounded the project? How did the partnership with the Asian Community Development Corporation come about, and who were some of the other partners? How did those relationships develop—and how is that part of the project?

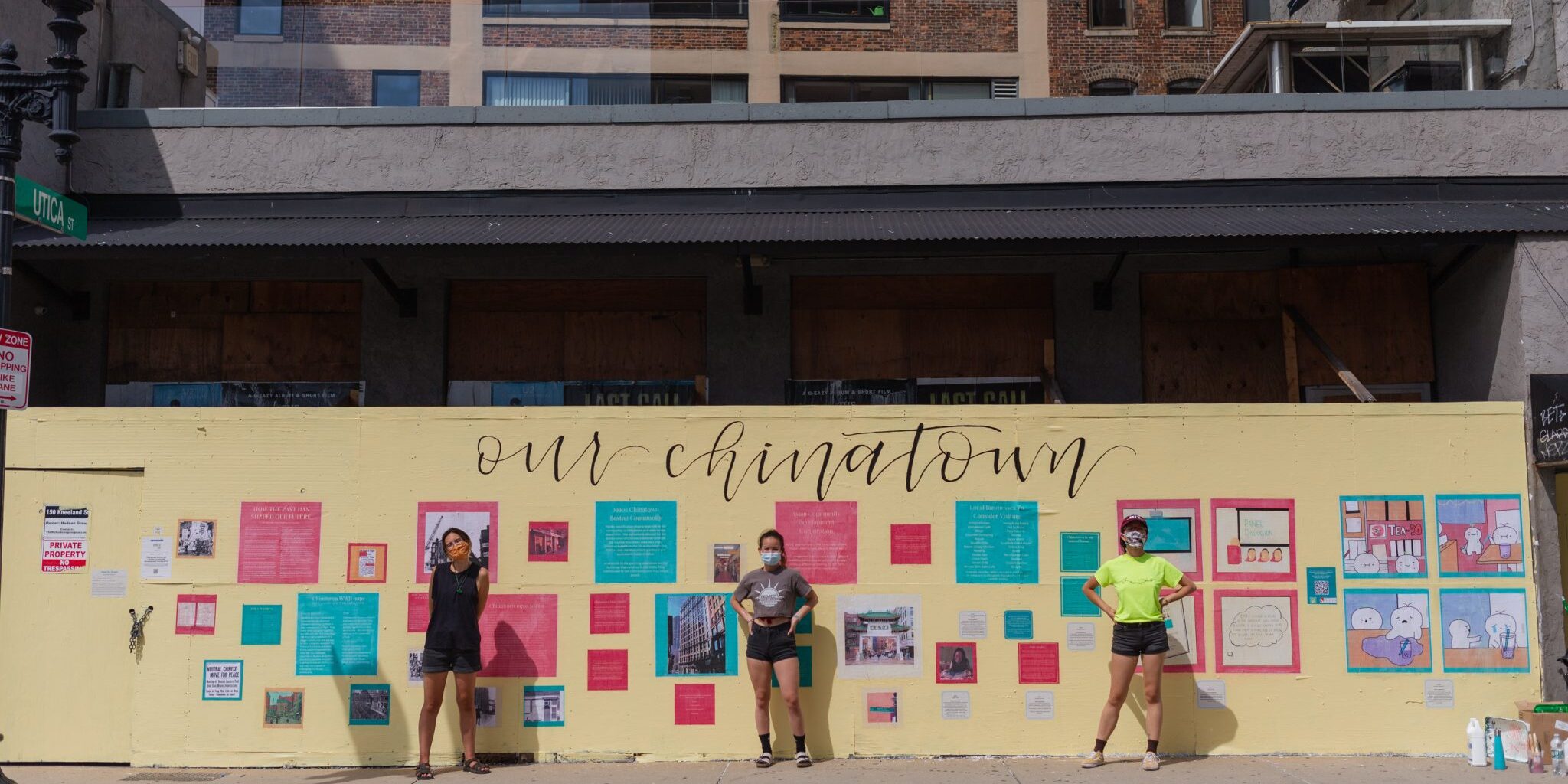

Crystal: The Partnership with Asian CDC came about through Residence Lab. We called up Jeena [Jeena Hah, Director of Programs & Design at ACDC] to see if Asian CDC would be willing to be a partner on this project. We also partnered with five different youth groups around Chinatown. For example, we worked with the Asian CDC’s placekeeping interns on the “Our Chinatown” mural.

Emma: I'm especially curious about the work of cultivating those relationships. As you've noted, you had some relationships already through prior work with ACDC and Residence Lab. But what does it take to make the work of relationship-building both ethical and generative?

Lily: When you do any type of socially engaged work, you sign up for a long-term commitment, even if your project is supposed to end in six months or two months or a year. You sign up for a longer-term commitment, because you nurture those relationships, and you work with people – and people don't have timelines. We both realized that residents and organizations in Chinatown have baggage about what it means for outsiders, for non-residents, to come in and want to tell stories or take stories, or just to make projects about the community in general.

We were blessed to have a partnership ACDC from the jump, and especially Jeena Hah, who is the Director of Programs and Design. To have her at ACDC as our advocate has been a blessing. We also tried to figure out the relationships among all of these different community organizations: activists, service organizations, tenants’ organizations. It was important for us to understand their place within the ecosystem of Chinatown. For me, it was also about showing up for folks in capacities that's not just as an artist, but as someone who goes to the neighborhood cleanup event or the local community meeting—those ways of showing up are important because it's about nurturing those relationships. As any sort of cultural worker, you’re working with people's humanity. And you need to acknowledge people's humanity and get to know people on an individual level.

Crystal: What Lily said was exactly right. There was a fatigue with artists doing storytelling projects in Chinatown, and I think a lot of communities feel that way, too. So, we had to acknowledge that fatigue and figure out how it would affect the design of the project. We've always seen ourselves as facilitators of projects, where community members are creators. The “Our Chinatown” mural, for example, was youth-led and youth-created. We were just giving them some skills.

Similarly, with the storytelling workshops that we did with young people, they collected from their connections in Chinatown, and we gave them interviewing tips and recording tips like how to find the memo app on your phone [laughter]. We’ve tried to frame ourselves as facilitators rather than leaders of projects, and make sure that young people have ownership over the projects. That perspective and approach came from our experience in Residence Lab, where we weren't centering ourselves as artists. It was a collaborative effort.

Emma: I appreciate that framing. It’s not a “project,” and it’s not about organizations and institutions. It’s a shared experience with other people. Building on that, what is it about working with young people—and specifically about the work of storytelling and oral history—that helps resist the “strategic forgetting” that, as you have written, “happens on gentrifying lands”? And can you talk about how you see that forgetting playing out in the neighborhood today?

Lily: I'm thinking about the last part of your question first. We know that Chinatowns across the U.S., including in Boston, have been sites of gentrification and displacement. Because of that, the memories of the people who have lived and shaped these communities are embedded in the land but are often forgotten because people have been displaced. In her book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer quotes Gary Nabhan on the idea and the importance of “re-story-ation.” Restoring the stories in the land is an important part of healing.

History is written into places. In Chinatown and across Boston, you see that in monuments, or street names. Crystal and I both live near Columbus Street, for example. But there are places where history is not written into the land. In Chinatown, we have that big Chinese-style gate, but you don't see as much the history of Little Syria, which was in the place that's now Chinatown.

Crystal: Within that question about strategic forgetting there is also something about community preservation, and how that relates to advocacy. Storytelling projects can generate care for a neighborhood. For example, there was a project called “Love Letters to Chinatown,” which I really loved. How can we write our cares, write our memories, write our existence—and also build networks of advocacy? You also asked about how youth, in particular, why we work with youth, how this work impacts youth. Young people have been leaders in combatting anti-Asian racism and have been speaking out about this since the pandemic hit. For example, Boston public school students wrote a letter advocating for more awareness about the anti-Asian hate that they were experiencing. The stories that we captured during the pandemic absolutely capture that moment and that sentiment as well. The students were experiencing this racism in March 2020—it was very pertinent before it was in the news.

I’m also thinking about a comic by Wendy Zhu in the “Our Chinatown” mural; she says that her age doesn’t discredit her perspective or her story, and I think that's the power of storytelling projects. Young people can gain the confidence to know that they can their actions and their advocacy have real impacts on their community, and that their effort can shape their community in the future.

Emma: Where do you see the need for advocacy in the neighborhood today? You've talked about anti-Asian racism that has been especially present for the last year. Where do you see those current needs in the community, and how is this project in conversation with not just present injustices but also those from the past—and the ways that those injustices are linked?

Lily: ACDC has a strategy called ANCHOR, which uses creative placekeeping as a way to anchor the borders of Chinatown. The idea is that the borders of any neighborhood are like a shoreline, vulnerable to erosion. In Chinatown we have South Station and the Financial District on one side, downtown expanding on another side, and then there are the highways. Issues of land and space are always at the center of the advocacy conversations in Chinatown. For example, Parcel R-1, the last piece of public land in the neighborhood, is up for redevelopment. The conversation about the library is emerging once again, and folks are asking for a public library in whatever new space is developed. There are always conversations around housing and affordable housing. Talking about the highway also touches on this: what it has done to Chinatown, and how we can use the stories about the effects of the highway to think about our relationship to our neighborhood, and what responsibility the folks who have caused us harm in the past have to our well-being in the present?

Emma: Thank you for laying that out; it helps situate the project, especially for people who may be less familiar with the neighborhood’s social and physical fabric.

Lily: There’s another thing I’d like to add. In the early days of the project, Crystal and I spoke with Tunney Lee, who unfortunately recently passed, but has been a huge community advocate. He was a professor at MIT and an architect, and an amazing person. I remember it distinctly: we were talking with him about anchoring borders, interpretation, etc. And he stopped and said, we keep talking about how Chinatown's shrinking, Chinatown's being gentrified, but when's the last time you've seen a McDonald's get replaced by a hot pot restaurant? His point was that, in a lot of ways, we don't tell the story of how Chinatown as a community has fought for its own livelihood—and has won. Time and time again it's won back land for affordable housing, community centers, and space for local organizations. Michael Liu, who just wrote this book called Forever Struggle about the community struggles in Chinatown, said to me that he did an inventory of how many community organizations were in Chinatown, and there was something like three community organizations for every block in Chinatown. The way that we tell the story is important; there are a lot of deficit narratives being told about not only Chinatown but pretty much any community of color. I think we have an obligation to also share the stories of strength and power, because those are happening all the time.

Crystal: Exactly. We started thinking this was a project about anti-displacement and about unearthing this painful history. But in advocacy it needs to be both/and: it needs to be the stories of resilience and the victories, as well as an acknowledgment that development projects have displaced folks. We're holding both stories. But that’s not part of our usual narrative. If community members are telling their own story, then it won't be a deficit model. Because yes, injustice and oppression is real and it is happening, but it can be really demoralizing if that's the only story you hear. What does that do to a community, if the story of deficiency is the only narrative that's being told?

Emma: Thank you so much for noting that and for pointing out that gap in my own thinking, which is indicative of the problem. What you're describing sounds like a healthy neighborhood—a great place to live, with strong civic infrastructure. For me, this raises questions about the kinds of places we hold up as models, particularly as planners and people who do future visioning work.

I'm wondering if we can shift gears a little bit to talk about COVID. What has it meant for you as artists to pivot this project that is so rooted in place and into the digital realm? And what are you taking away from that experience as we begin to transition out of the pandemic—and into a future that will likely involve a mixture of in-person and virtual experiences?

Crystal: Massachusetts shut down on March 12, 2020, and our workshop was set for the following Monday. Lily and I did a lot of reworking of the curriculum. We couldn't use physical books, but there were a lot of digital tools that we were able to use. Everyone hit the ground running. Youth groups didn't miss a beat. People were still gathering, but in digital space, so in that way it felt like we were still in community, even though it felt more disconnected.

We also tried to find new ways of forming connections. We mailed Story Kits to residents, which was a fun way to have a physical connection and show community care, and to collect their reflections and their artwork about the current moment.

Lily: I’m also realizing how lucky we were to step into the existing civic infrastructure, like local youth programs. We met so many amazing youth workers who were doing tremendous lifts to move their programs online and make sure their students had the necessary tech. And a lot of the organizations we work with already had staff capacity for interpretation and were able to move that online.

At the same time, I’ve observed that as community meetings have moved online, there have been difficulties around access. The folks who have the least amount of tech access, especially elders, folks who only speak Chinese or other languages—it’s been really difficult for them.

Coming back to the Story Kits: because we weren't doing in-person things, we never built the Story Cart, because we weren't going to be outside. So we had extra funds that we wanted to redistribute. When we mailed the Story Kits, we paid everyone for their stories. We were able to do this because we were saving costs and other parts of the project. We also adapted some folks’ responses to the Story Kits into postcards and we sent them out with grocery coupons, which ACDC helped us do. For Chinatown residents who were especially hard hit by the pandemic, our project responded to that, too.

Emma: I love that, and thank you for addressing that aspect of what it means to shift gears in this moment. It's not just about translating what was previously going to be an in-person experience to Zoom, it's about rethinking why we're doing the things we're doing, and how we can care for each other better—and in new ways, too.

In our remaining time, I’d love to know what's next for the Story Cart. And what's next for you as artists, educators, and facilitators? Are there any new place-based projects you’re working on?

Lily: For the Story Cart, we are going to have a pop up event this September as part of Hudson Street Stoop programming. Hudson Street Stoop is a project by Gianna Stewart in partnership with ACDC at One Greenway, which is a small park. We'll have a physical cart (fingers crossed!), and that’ll be a chance for us to share the stories we collected over the past year, so folks will be able to come by pick up a copy of the zine. We'll also have a virtual showcase, probably sometime around September, for folks to share their stories and do some processing and reflection about the past year.

Crystal: We’re hoping to work with some young people over the summer, to help us put together these stories and share them. In my role with the Design Studio for Social Intervention, we're leading the community-engaged portion of the redesign of the Union Square plaza and streetscape in Somerville. We’ve identified a community theme, and we're doing a lot of workshops building community knowledge and deeply investigating community wisdom to figure out how that can shape the design process.

Lily: I’m working on a project called Washing, which is about the legacy of the two highways that run through Chinatown (I-93 and I-90). I’m creating it with a group of four Chinatown residents Dianyvet Serrano, Chu Huang, Charlene Huang, and Maggie Chen, and we have been working together for five months collecting oral histories, making video art, doing sound design, doing video editing, and making a projection installation that will open on May 29.

I’m also wrapping up a research position at the Data + Feminism Lab at MIT. We just released a zine about Christopher Columbus and his memorialization in the U.S. It's a collection of case studies about contestations to his memorialization called “We Never Wanted Him Here: A Brief History of Protest Takedowns and Counterproposals to the Commemoration of Christopher Columbus.”

Emma: I can't wait to check out all of these projects, and if there's a copy I can get of that zine, that would be amazing. Thank you so much for sharing this time and your experiences with us. We really appreciate it.

Editors' Note:

We first met Lily after she attended one of the convenings for the Arts & Culture Discussion Series, and her project came to mind as we reflected on the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic has been felt most acutely by people on either end of the generational divide. The disproportionate loss of elders has had a devastating impact on collective memory. Meanwhile, youth who missed out on core life experiences rose to the occasion by organizing mutual aid societies and protesting for racial justice.

As we consider ways to support collective healing from the past year, the Chinatown Story Cart offers lessons for the ways in which we can strengthen community ties as we safely reconnect in public space with a renewed attention to redressing racism and historic inequities.