Welcome Home Essex

Welcome Home Essex

Welcome Home Essex is a community and data-driven Housing Production Plan (HPP) for the future of housing in Essex. This HPP will expand housing diversity, affordability, and opportunity in the community and region. The Town has hired the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) to provide technical assistance services to complete the HPP.

The Town and MAPC (the Planning Team) together will work with residents and stakeholders throughout the process to set the vision and direction of housing policy in Essex for the next five years.

Questions? Want to Get Involved?

Contact John Cruz, AICP, Senior Housing and Land Use Planner at MAPC ([email protected])

About the Plan

Welcome Home Essex will meet all the requirements of a Housing Production Plan and will be the town’s first HPP. HPPs help communities understand their housing needs, set housing goals, and identify strategies to achieve them. Through this process, we will work to expand and diversify Essex’s housing stock while also increasing affordability for people at a range of incomes. The Town of Essex is undertaking is undertaking this plan via the office of the Town Administrator with the help of the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC), the regional planning agency for Greater Boston.

This planning process is meant to engage people from all over Essex, especially groups that have been historically underrepresented by urban planning processes. This includes people of color, low-income residents, renters, and others.

Subscribe to the Project Email List

Always be up to date on this project!

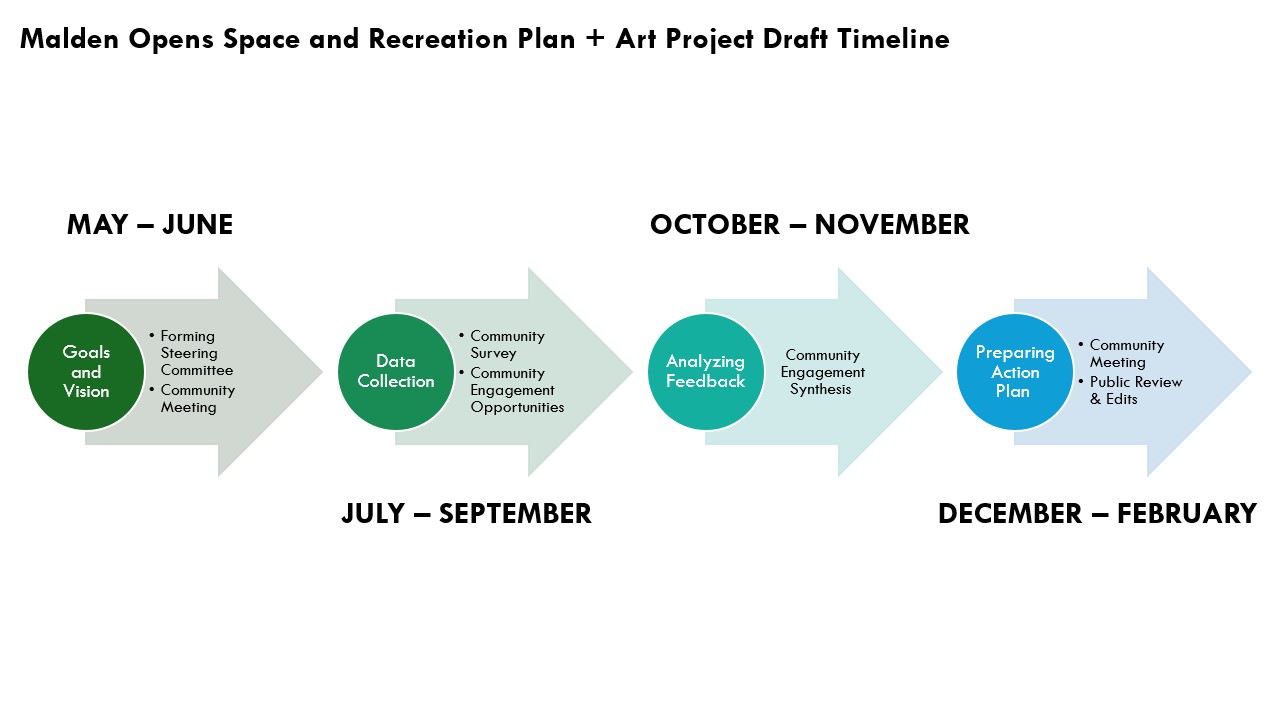

Timeline

Fall – Winter 2024

Exploring and data gathering

Completing a Housing Needs Assessment

Examining constraints and opportunities

Land use / zoning audit

Draft site selection

Spring – Summer 2025

Draft Goals and Strategies

Refine site selection

Fall – Winter 2025

Refine goals and strategies

Draft HPP and executive summary

End of 2025

Refine HPP draft

Public comment period and hearing on HPP

HPP is sent to EOHLC for approval

What is a Housing Production Plan (HPP)?

Housing Production Plans are a specific plan type defined under Massachusetts state law (MGL Chapter 40B) and regulated by the state’s Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities. To go into effect, the plan must be adopted by the Town and approved by EOHLC.

HPPs must include the following elements:

- Assessment of housing needs and demand

- Analysis of development constraints

- Identification of opportunity sites for new housing development

- Housing goals for the next five years, including numeric targets for new housing production

- Specific policies and programs that will help achieve housing goals

Having an active HPP will support Essex’s eligibility to receive state grants. Other benefits of creating an HPP are summarized below.

Meet local housing need

First and foremost a housing production plan is used to identify and address unmet housing need. Through this process, Essex will gather a comprehensive set of data and engage the public to identify this need. The HPP will include goals and strategies for the Town and the Essex Housing Authority (EHA) to meet local housing needs.

Proactively influence development

An HPP is also a strong guide for housing development that allows the community to decide what type of housing is needed and where it should go. State law M.G.L Chapter 40B prompts each community to have 10% of its housing stock count on the subsidized housing inventory (SHI). If this target isn’t met, Affordable Housing development can be approved without complying with local zoning regulations. While Chapter 40B is often not a popular policy in many communities it is the law. Essex’s SHI is at 2.58% making the Town susceptible to 40B development even though no 40B developments have taken place in Essex yet. An updated HPP will position Essex to get out front and plan for housing development rather than reacting to a 40B development once it’s proposed.

Comply with Chapter 40B

With a HPP, Essex can still comply with Chapter 40B without reaching the 10% SHI target. If the updated HPP is locally adopted and approved by the state, Essex can achieve safe harbor in the following ways:

- 2-year safe harbor if SHI is increased by 1% in one calendar year

- 1-year safe harbor is SHI is increased by 0.5% in one calendar year

What is Affordable Housing?

When most people talk about housing affordability, they usually are referring to housing that works within their budget. When housing planners talk about “Affordable Housing” (with a capital “A” and “H”), they are referring to housing that by law can only be rented or sold to low-income households, and moderate-income households in some cases, without these households paying more than 30% of their income. A household is “housing cost-burdened” when it pays 30% or more of its income on housing costs. Paying this much for housing often means a household will face tough financial decisions and may not be able to afford other necessities such as food, medicine, and transportation.

Affordable Housing has restrictions on its deed that preserve affordability for decades or in perpetuity, ensuring that income-eligible households can stay in their communities. Historically, Affordable Housing was built by the government, but today it is typically built by nonprofit organizations using government subsidies and tax credits. Market-rate developers also produce Affordable Housing units as required by local inclusionary zoning policies, incorporating affordable units into market-rate developments.

Eligibility to live in deed-restricted Affordable Housing is based on income status, which is determined by comparing a household’s total pre-tax income and the number of people in the household to the Area Median Income (AMI). AMI is the median income for households across the Greater Boston region, including Essex and is $148,900 for the year 2024. A household is considered “low-income” if its annual income is 80% or less of the AMI, which is $91,200 for a single person and $130,250 for a family of four. Currently, 2.58% of Essex’s housing is in the SHI as affordable.

| Household Size | Area Median Income (AMI) | 80% AMI (Low-Income) | 50% AMI (Very Low-Income) | 30% AMI (Extremely Low-Income) |

| 1-Person | $114,000 | $91,200 | $57,100 | $34,300 |

| 2-Person | $130,250 | $104,200 | $65,300 | $39,200 |

| 3-Person | $146,563 | $117,250 | $73,450 | $44,100 |

| 4-Person | $162,813 | $130,250 | $81,600 | $48,950 |

Source: 2024 HUD Area Median Income Limits for Greater Boston

Learn more about HPPs and Affordable Housing:

Resources

Committee Meeting Re-Caps

To ensure that all the committee meetings have content available to the public, we will be posting the PowerPoint presentations MAPC gives to the committee at each meeting in this section. The presentations will be in PDF format for you to download and review.

Committee Meeting #1, October 10, 2024

Project and process overview, HPP overview

Presentation

Committee Meeting #2, December 9, 2024

Housing Needs Assessment Data, Prep for Public Event

Presentation

January 30, 2025 Webinar

On January 30, 2025, MAPC and Essex held a webinar to discuss key findings from the Housing Needs Assessment, share the housing production plan process, and gain insights from residents.